The First Steps, by Georgios Jakobides, 1892. Public Domain

When was the last time you thought about walking? Not as a form of transportation, but the physical act of striding forward, upright on two legs. Walking is utterly human. We’re the only species that does it. It’s a basic form of mobility and the most egalitarian of activities. It’s absolutely free and almost everyone can do it. Moving on two legs keeps our bodies healthy. It focuses our minds and, as recent research confirms, also makes us happy.

From our earliest months onward, walking is linked to learning. Although they lack the strength and balance to do it, infants already know how to walk. Babies spend the better part of their first year scooching, crawling, pulling themselves up, striving to be vertical so that they can more easily explore the world around them--which is why a baby’s first steps are pure joy. You don’t remember yours, but if you’re a parent, an aunt, uncle or grandparent, you’ve shared the exhilaration of this moment. When it happens, you’re reminded that walking is an extraordinary act.

But because it’s inherent, it’s ordinary. The toddler becomes an expert walker and the thrill is gone. Once the intense drive to get up and put one step in front of another is satisfied, walking becomes more like breathing--essential, but taken for granted. An injury or illness that puts you on crutches or in a wheelchair may remind you that walking is in fact, miraculous. But for the most part, it’s barely considered.

This disregard for walking can be found in the dictionary’s definition of pedestrian. Just below the phrase “someone who walks”, is the more pejorative “lacking inspiration or excitement.” Centuries of western art confirm the fact that walking is a humble act. Peasants walk, while the wealthy and powerful ride, their authority conveyed from an elevated position in a carriage or astride a horse. Few folktales communicate the aspirational quality of riding better than Cinderella, whose fairy godmother understood that a lowly servant girl required more than a gown and a pair of glass slippers to be allowed entry to the upper echelons of society. To turn heads and win the heart of the prince, she would need an extravagant carriage.

Since the domestication of animals and invention of the wheel, we’ve aspired to cover ground faster and with less effort. For millennia, horses, donkeys chariots, wagons, coaches, steam and electricity were harnessed to lighten our load and quicken the pace of travel until finally, in mid-20th century America, fossil fuels and the internal combustion engine combined to spell the beginning of the end for walking as a form of transportation.

In 1941, the Lions Club of Rutland produced a movie set in its downtown. Our Rutland was meant to be a fond hello and show of support for (presumably Vermont) soldiers training at a Florida army base. This joyful celebration of hometown pride features clips of bustling streets, merchants, workers, homeowners, churchgoers, fire fighters--even the high school baseball team and marching band--posing and waving to the camera as they go about their business on a spring day.

What’s striking about the film is the high level of activity on Rutland’s streets and sidewalks--far more than you would see today. Perhaps many of the people shown walking on Center Street and Merchants’ Row that day knew about the film and came to mark their place in it. But you can see evidence for the flood of pedestrians in almost every frame of the 30-minute film. The camera pans the city’s buildings, showcasing a dense array of businesses--pharmacies, jewelers, cinemas, department stores, restaurants, beauty salons, to name a few. It lifts its gaze upward to the social clubs and offices above street level.. It lingers on the train station, the nearby courthouse, hospital, high school, churches, and homes as it paints a picture of a complete, self-contained community, knit together by sidewalks. In 1941, Rutland residents lived close to downtown and had every reason to walk there. It was most likely the center of their world.

It’s mesmerizing to watch the flow of walkers captured in an ordinary moment of their lives, and enjoy the parade of war-era style--military uniforms, leather shoes, suits, tweeds, nylons, cardigans, hair rolls, and cigarettes. Although it was intended for immediate consumption, the film is now a time capsule. These Rutland residents were saying hello from a specific place. Now they wave to us from a specific time.

The 1940s and the war that shaped that decade accelerated many changes in American life. Transportation was one of them. 1941 marked a transition between a transit-based system, to one based on private automobiles. Cars had become more common, but rail, bus, and pedestrian infrastructure was robust and using those modes was still ingrained in Vermonters’ habits. Rutland residents had far more travel options than we enjoy today, including one few contemporary Americans can take advantage of--walking.

Looking back, from our car-dependent world, it’s easy to see how it all went wrong--how cities like Rutland and almost every community in the country dismantled, through active measures or entropy, the urban fabric of density and economic diversity that made downtowns the center of life and walking an essential activity. In 2019 we tend to approach traffic and parking with a sense of exhausted necessity, but 78 years ago, without knowing what was at stake, a “gee isn’t this fun” embrace of the car was understandable. In an early scene that shows a beaming couple in a late-model convertible, navigating a downtown street, riding seems much more glamorous than walking. The challenges of fitting cars into a 19th century downtown are already evident in the film, with shots of traffic cops, walls of on-street parking, and signs of a fender bender. But despite the fact that cars are everywhere, they don’t seem necessary.

This time capsule from the mid-20th century busts the myth that living in the countryside, far from other people is the Vermont way. It’s a reminder that an urban lifestyle--walking a lot, sharing space with neighbors, and enjoying a rich community life often experienced on a sidewalk--was and can again be a significant part of our identity. We may not be able to bring back the pharmacies and department stores of 1941, but we can make a huge impact on the walkability of our communities by the transportation investments we make today.

Rail, buses and sidewalks created and fed the dense urban fabrics of places like Rutland. Highways, parking lots and garages drained them. Our transportation spending of the past 80 years focused on moving and storing cars. It allowed everyone to ride but created a world where few people can walk. Putting everything we’ve got into downtowns, while funding rail, bus, bike and pedestrian infrastructure will give us the best of both worlds--a system that combines riding with the extraordinary and miraculous act of walking.

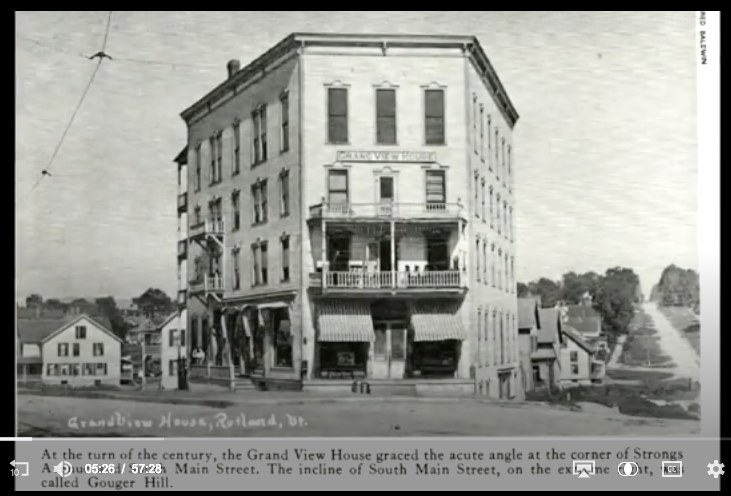

Three different eras of development at one Rutland intersection. In 2017, the Rutland Historical Society revised Our Rutland, adding current and past images of many of the film’s featured locations as well as narration by member Raymond Mooney. It’s a fascinating view of how the city has changed, and offers glimpses of the impact automobiles have had on its built environment. Watch the RHS’s revised version of “Our Rutland” on file at the Vermont Historical Society’s online archives..